Over fifty years ago, Michael Fürst challenged conventional norms to become what is believed to be the first Jewish soldier to join the German armed forces – the Bundeswehr – following World War Two. Fast forward to today, the Bundeswehr is home to an estimated 300 Jewish serving personnel, who, like Michael, resist the weight of history.

The harsh shadows of yore still cast a pall over the German military landscape, and the malicious spectre of anti-Semitism has yet to be completely exorcised. In today’s context of heightened vigilance, a conversation discussing Nazi wartime medals and anti-Semitism would lead to an immediate expulsion from the military. However, in the late 1960s, Michael recalls fellow soldiers exhibiting their Nazi wartime medals with no fear of retribution.

Anne, a German Jewish soldier, vividly speaks of her decision to enlist in the military at a tender age of 15. Her decision was met with incredulity and questions trailed after her, tarnishing her school days with accusations of allying with the oppressors of the Holocaust.

Hailing from her post as the spiritual lead of the military chaplaincy is Zsolt Balla. Conceived after a historic agreement in 2019 between Germany’s Central Council of Jews and the Ministry of Defence, this development is lauded as a positive triumph for Jewish soldiers. This establishment offers not only religious care to Jewish soldiers but also offers insightful voluntary classes about Judaism to interested Bundeswehr members.

This feat didn’t quash the scepticism seeping through the cracks of acceptance. Michael Fürst, a highly decorated member of the Jewish Community, remains doubtful about the necessity of such numerous military rabbis. However, he adds that the establishment of the chaplaincy is indeed a stride in the right direction.

The presence of Jews in the German military breaks boundaries and stirs controversial tongues. This reality breeds questions that tread on sensitive memories, evoking grating discussions involving anti-Semitism, Holocaust, and identity. In response to such queries, Zsolt Balla offers a philosophically balanced view; he champions the idea that in any armed force populated by volunteers, one would inevitably encounter individuals with conservative views.

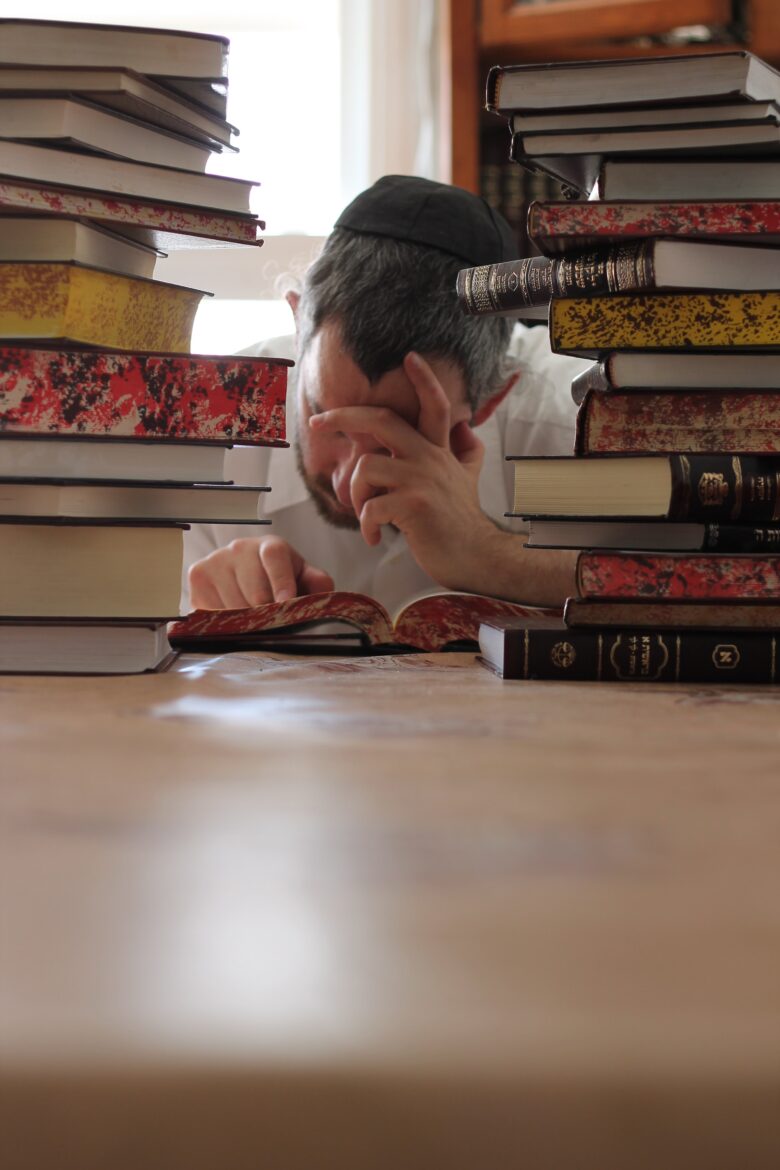

Fellow Jewish Bundeswehr member, Johannes, finds much in common between Jewish teachings and the values advocated by the German military. His sentiments mirror Michael’s recollections of how he perceives his identity as being simultaneously German and Jewish.

A five-decades-old decision still reverberates in today’s context. Despite facing painful remembrance, Jews are stepping forward to safeguard their homeland, Germany. Dispelling notions of fragmented identities, they defend principles that bear a unified identity coloured by human rights, constitutional safeguards, and democracy.

Anne sheds light on this transformation when she speaks of how the values of society and constitutional principles are enjoined in the safeguarding role of the Bundeswehr and different from the morally violated ideals of the Nazis.

In more concrete terms, as Michael engages in fond reminiscences of boldly opting to serve the Bundeswehr, he casually brushes off the unpleasantries sprouting from his unique choice. Michael’s story and now, those of other Jews subsequently choosing to stand with their homeland in defiance of the past, echo a tale of victory over historical burdens. It’s a saga of erasing old biases and treading new paths all under the banner of harmonious co-existence.

Echoing Zsolt Balla, it is perhaps that over time we have gained sufficient historical distance that prevents us from being paralysed by the past, allowing us to make strides towards uncharted territories. While the world follows Germany’s accountable confrontation of its deeds of World War II and the Holocaust, the story of Jews in the German Military stands out as an apt symbol of reconciliation and progress.